Identification. Though there is archaeological evidence that societies have been living in

Nigeria for more than twenty-five hundred years, the borders of modern Nigeria were not created

until the British consolidated their colonial power over the area in 1914.

The name Nigeria was suggested by British journalist Flora Shaw in the 1890s. She referred to the

area as Nigeria, after the Niger River, which dominates much of the country's landscape.

The word niger is Latin for black.

More than 250 ethnic tribes call present-day Nigeria home. The three largest and most dominant

ethnic groups are the Hausa, Yoruba, and Igbo (pronounced ee-bo). Other smaller groups include

the Fulani, Ijaw, Kanuri, Ibibio, Tiv, and Edo. Prior to their conquest by Europeans, these

ethnic groups had separate and independent histories. Their grouping together into a single

entity known as Nigeria was a construct of their British colonizers. These various ethnic groups

never considered themselves part of the same culture. This general lack of Nigerian nationalism

coupled with an ever-changing and often ethnically biased national leadership, have led to sever

e internal ethnic conflicts and a civil war. Today bloody confrontations between or among members

of different ethnic groups continue.

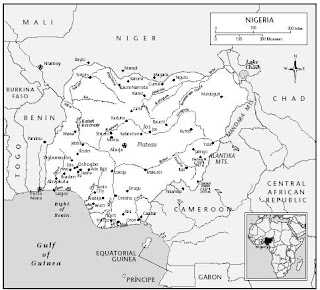

Location and Geography. Nigeria is in West Africa, along the eastern coast of the Gulf of Guinea,

and just north of the equator. It is bordered on the west by Benin, on the north by Niger and

Chad, and on the east by Cameroon. Nigeria covers an area of 356,669 square miles

(923,768 square kilometers), or about twice the size of California.

Nigeria has three main environmental regions: savanna, tropical forests, and coastal wetlands.

These environmental regions greatly affect the cultures of the people who live there. The dry,

open grasslands of the savanna make cereal farming and herding a way of life for the Hausa and

the Fulani. The wet tropical forests to the south are good for farming fruits and vegetables—main

income producers for the Yoruba, Igbo, and others in this area. The small ethnic groups living

along the coast, such as the Ijaw and the Kalabari, are forced to keep their villages small due

to lack of dry land. Living among creeks, lagoons, and salt marshes makes fishing and the salt

trade part of everyday life in the area.

The Niger and Benue Rivers come together in the center of the country, creating a "Y" that splits

Nigeria into three separate sections. In general, this "Y" marks the boundaries of the three

major ethnic groups, with the Hausa in the north, the Yoruba in the southwest, and the Igbo in

the southeast.

Politically, Nigeria is divided into thirty-six states. The nation's capital was moved from Lagos

, the country's largest city, to Abuja on 12 December 1991. Abuja is in a federal territory that

is not part of any state. While Abuja is the official capital, its lack of adequate infrastructure

means that Lagos remains the financial, commercial, and diplomatic center of the country.

Demography. Nigeria has the largest population of any African country. In July 2000, Nigeria's

population was estimated at more than 123 million people. At about 345 people per square mile,

it is also the most densely populated country in Africa. Nearly one in six Africans is a Nigerian.

Despite the rampages of AIDS, Nigeria's population continues to grow at about 2.6 percent each

year. The Nigerian population is very young. Nearly 45 percent of its people are under age

fourteen.

With regard to ethnic breakdown, the Hausa-Fulani make up 29 percent of the population, followed

by the Yoruba with 21 percent, the Igbo with

18 percent, the Ijaw with 10 percent, the Kanuri with 4 percent, the Ibibio with 3.5 percent, and the Tiv with 2.5 percent.

Major urban centers include Lagos, Ibidan, Kaduna, Kano, and Port Harcourt.

Linguistic Affiliations. English is the official language of Nigeria, used in all government interactions and in state-run schools. In a country with more than 250 individual tribal languages, English is the only language common to most people.

Unofficially, the country's second language is Hausa. In northern Nigeria many people who are not ethnic Hausas speak both Hausa and their own tribal language. Hausa is the oldest known written language in West Africa, dating back to before 1000 C.E.

The dominant indigenous languages of the south are Yoruba and Igbo. Prior to colonization, these languages were the unifying languages of the southwest and southeast, respectively, regardless of ethnicity. However, since the coming of the British and the introduction of mission schools in southern Nigeria, English has become the language common to most people in the area. Today those who are not ethnic Yorubas or Igbos rarely speak Yoruba or Igbo.

Pidgin, a mix of African languages and English, also is common throughout southern Nigeria. It basically uses English words mixed into Yoruban or Igbo grammar structures. Pidgin originally evolved from the need for British sailors to find a way to communicate with local merchants. Today it is often used in ethnically mixed urban areas as a common form of communication among people who have not had formal education in English.

Symbolism. Because there is little feeling of national unity among Nigeria's people, there is little in terms of national symbolism. What exists was usually created or unveiled by the government as representative of the nation. The main national symbol is the country's flag. The flag is divided vertically into three equal parts; the center section is white, flanked by two green sections. The green of the flag represents agriculture, while the white stands for unity and peace. Other national symbols include the national coat of arms, the national anthem, the National Pledge (similar to the Pledge of Allegiance in the United States), and Nigeria's national motto: Peace and Unity, Strength and Progress.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. Every ethnic group in Nigeria has its own stories of where its ancestors came from. These vary from tales of people descending from the sky to stories of migration from far-off places. Archaeologists have found evidence of Neolithic humans who inhabited what is now Nigeria as far back as 12,000 B.C.E.

The histories of the people in northern and southern Nigeria prior to colonization followed vastly different paths. The first recorded empire in present-day Nigeria was centered in the north at Kanem-Borno, near Lake Chad. This empire came to power during the eighth century C.E. By the thirteenth century, many Hausa states began to emerge in the region as well.

Trans-Sahara trade with North Africans and Arabs began to transform these northern societies greatly. Increased contact with the Islamic world led to the conversion of the Kanem-Borno Empire to Islam in the eleventh century. This led to a ripple effect of conversions throughout the north. Islam brought with it changes in law, education, and politics.

The trans-Sahara trade also brought with it revolutions in wealth and class structure. As the centuries went on, strict Islamists, many of whom were poor Fulani, began to tire of increasing corruption, excessive taxation, and unfair treatment of the poor. In 1804 the Fulani launched a jihad, or Muslim holy war, against the Hausa states in an attempt to cleanse them of these non-Muslim behaviors and to reintroduce proper Islamic ways. By 1807 the last Hausa state had fallen. The Fulani victors founded the Sokoto Caliphate, which grew to become the largest state in West Africa until its conquest by the British in 1903.

In the south, the Oyo Empire grew to become the most powerful Yoruban society during the sixteenth century. Along the coast, the Edo people established the Benin Empire (not to be confused with the present-day country of Benin to the west), which reached its height of power in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

As in the north, outsiders heavily influenced the societies of southern Nigeria. Contact with Europeans began with the arrival of Portuguese ships in 1486. The British, French, and Dutch soon followed. Soon after their arrival, the trade in slaves replaced the original trade in goods. Many of the coastal communities began selling their neighbors, whom they had captured in wars and raids, to the Europeans in exchange for things such as guns, metal, jewelry, and liquor.

The slave trade had major social consequences for the Africans. Violence and intertribal warfare increased as the search for slaves intensified. The increased wealth accompanying the slave trade began to change social structures in the area. Leadership, which had been based on tradition and ritual, soon became based on wealth and economic power.

After more than 350 years of slave trading, the British decided that the slave trade was immoral and, in 1807, ordered it stopped. They began to force their new found morality on the Nigerians. Many local leaders, however, continued to sell captives to illegal slave traders. This lead to confrontations with the British Navy, which took on the responsibility of enforcing the slave embargo. In 1851 the British attacked Lagos to try to stem the flow of slaves from the area. By 1861 the British government had annexed the city and established its first official colony in Nigeria.

As the non slave trade began to flourish, so, too, did the Nigerian economy. A new economy based on raw materials, agricultural products, and locally manufactured goods saw the growth of a new class of Nigerian merchants. These merchants were heavily influenced by Western ways. Many soon became involved in politics, often criticizing chiefs for keeping to their traditional ways. A new divide within

Africa.

the local communities began to develop, in terms of both wealth and politics. Because being a successful merchant was based on production and merit, not on traditional community standing, many former slaves and lower-class people soon found that they could advance quickly up the social ladder. It was not unusual to find a former slave transformed into the richest, most powerful man in the area.

Christian missionaries brought Western-style education to Nigeria as Christianity quickly spread throughout the south. The mission schools created an educated African elite who also sought increased contact with Europe and a Westernization of Nigeria.

In 1884, as European countries engaged in a race to consolidate their African territories, the British Army and local merchant militias set out to conquer the Africans who refused to recognize British rule. In 1914, after squelching the last of the indigenous opposition, Britain officially established the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria.

National Identity. The spread of overt colonial control led to the first and only time that the ethnic groups in modern Nigeria came together under a commonly felt sense of national identity. The Africans began to see themselves not as Hausas, Igbos, or Yorubas, but as Nigerians in a common struggle against their colonial rulers.

The nationalistic movement grew out of some of the modernization the British had instituted in Nigeria. The educated elite became some of the most outspoken proponents of an independent Nigeria. This elite had grown weary of the harsh racism it faced in business and administrative jobs within the government. Both the elite and the uneducated also began to grow fearful of the increasing loss of traditional culture. They began movements to promote Nigerian foods, names, dress, languages, and religions.

Increased urbanization and higher education brought large multiethnic groups together for the first time. As a result of this coming together, the Nigerians saw that they had more in common with each other than they had previously thought. This sparked unprecedented levels of interethnic teamwork. Nigerian political movements, media outlets, and trade unions whose purpose was the advancement of all Nigerians, not specific ethnic groups, became commonplace.

Arts & Crafts Sale: Get $10 off your order of $40! Hurry offer expires 6.13.11!

As calls for self-determination and a transfer of power into the hands of Nigerians grew, Britain began to divest more power into the regional governments. As a result of early colonial policies of divide and conquer, the regional governments tended to be drawn along ethnic lines. With this move to greater regional autonomy, the idea of a unified Nigeria became to crumble. Regionally and ethnically based political parties sprang up as ethnic groups began to wrangle for political influence.

Ethnic Relations. Nigeria gained full independence from Britain on 1 October 1960. Immediately following independence, vicious fighting between and among political parties created chaos within the fledgling democracy. On 15 January 1966 a group of army officers, most of whom were Igbo, staged a military coup, killing many of the government ministers from the western and northern tribes. Six months later, northern forces within the military staged a countercoup, killing most of the Igbo leaders. Anti-Igbo demonstrations broke out across the country, especially in the north. Hundreds of Igbos were killed, while the rest fled to the southeast.

On 26 May 1967 the Igbo-dominated southeast declared it had broken away from Nigeria to form the independent Republic of Biafra. This touched off a bloody civil war that lasted for three years. In 1970, on the brink of widespread famine resulting from a Nigeria-imposed blockade, Biafra was forced to surrender. Between five hundred thousand and two million Biafran civilians were killed during the civil war, most dying from starvation, not combat.

Following the war, the military rulers encouraged a national reconciliation, urging Nigerians to once again become a unified people. While this national reconciliation succeeded in reintegrating the Biafrans into Nigeria, it did not end the problems of ethnicity in the country. In the years that followed, Nigeria was continually threatened by disintegration due to ethnic fighting. These ethnic conflicts reached their height in the 1990s.

After decades of military rule, elections for a new civilian president were finally held on 12 June 1993. A wealthy Yoruba Muslim named Moshood Abiola won the elections, beating the leading Hausa candidate. Abiola won support not only from his own people but from many non-Yorubas as well, including many Hausas. This marked the first time since Nigeria's independence that Nigerians broke from ethnically based voting practices. Two weeks later, however, the military regime had the election results annulled and Abiola imprisoned. Many commanders in the Hausa-dominated military feared losing control to a southerner. They played on the nation's old ethnic distrusts, hoping that a divided nation would be easier to control. This soon created a new ethnic crisis. The next five years saw violent protests and mass migrations as ethnic groups again retreated to their traditional homelands.

The sudden death of Nigeria's last military dictator, General Suni Abacha, on 8 June 1998 opened the door for a transition back to civilian rule. Despite age-old ethnic rivalries, many Nigerians again crossed ethnic lines when they entered the voting booth. On 22 February 1999 Olusegun Obasanjo, a Yoruba who ironically lacked support from his own people, won the presidential election. Obasanjo is seen as a nationalist who opposed ethnic divisions. However, some northern leaders believe he favors his own ethnic group.

Unfortunately, violent ethnic fighting in Nigeria continues. In October 2000, clashes between Hausas and supporters of the Odua People's Congress (OPC), a militant Yoruba group, led to the deaths of nearly a hundred people in Lagos. Many also blame the OPC for sparking riots in 1999, which killed more than a hundred others, most of them Hausas.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

With the influx of oil revenue and foreigners, Nigerian cities have grown to resemble many Western urban centers. Lagos, for example, is a massive, overcrowded city filled with traffic jams, movie theaters, department stores, restaurants, and supermarkets. Because most Nigerian cities grew out of much older towns, very little urban planning was used as the cities expanded. Streets are laid out in a confusing and often mazelike fashion, adding to the chaos for pedestrians and traffic. The influx of people into urban areas has put a strain on many services. Power cuts and disruptions of telephone service are not uncommon.

Nigerian architecture is as diverse as its people. In rural areas, houses often are designed to accommodate the environment in which the people live. The Ijo live in the Niger Delta region, where dry land is very scarce. To compensate for this, many Ijo homes are built on stilts over creeks and swamps, with travel between them done by boat. The houses are made of wood and bamboo and topped with a roof made of fronds from raffia palms. The houses are very airy, to allow heat and the smoke from cooking fires to escape easily.

Igbo houses tend to be made of a bamboo frame held together with vines and mud and covered with banana leaves. They often blend into the surrounding forest and can be easily missed if you don't know where to look. Men and women traditionally live in separate houses.

Much of the architecture in the north is heavily influenced by Muslim culture. Homes are typically geometric, mud-walled structures, often with Muslim markings and decorations. The Hausa build large, walled compounds housing several smaller huts. The entryway into the compound is via a large hut built into the wall of the compound. This is the hut of the father or head male figure in the compound.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Western influences, especially in urban centers, have transformed Nigerian eating habits in many ways. City dwellers are familiar with the canned, frozen, and prepackaged foods found in most Western-style supermarkets. Foreign restaurants also are common in larger cities. However, supermarkets and restaurants often are too expensive for the average Nigerian; thus only the wealthy can afford to eat like Westerners. Most urban Nigerians seem to combine traditional cuisine with a little of Western-style foods and conveniences. Rural Nigerians tend to stick more with traditional foods and preparation techniques.

Food in Nigeria is traditionally eaten by hand. However, with the growing influence of Western culture, forks and spoons are becoming more common, even in remote villages. Whether people eat with their hand or a utensil, it is considered dirty and rude to eat using the left hand.

While the ingredients in traditional plates vary from region to region, most Nigerian cuisine tends to be based around a few staple foods accompanied by a stew. In the south, crops such as corn, yams, and sweet potatoes form the base of the diet. These vegetables are often pounded into a thick, sticky dough or paste. This is often served with a palm oil based stew made with chicken, beef, goat, tomatoes, okra, onions, bitter leaves, or whatever meats and vegetables might be on hand. Fruits such as papaya, pineapples, coconuts, oranges, mangoes, and bananas also are very common in the tropical south.

In the north, grains such as millet, sorghum, and corn are boiled into a porridge-like dish that forms the basis of the diet. This is served with an oil based soup usually flavored with onions, okra, and tomatoes. Sometimes meat is included, though among the Hausa it is often reserved for special occasions. Thanks to the Fulani cattle herders, fresh milk and yogurt are common even though there may not be refrigeration.

Alcohol is very popular in the south but less so in the north, where there is a heavy Islamic influence. Perhaps the most popular form of alcohol is palm wine, a tart alcoholic drink that comes from palm trees. Palm wine is often distilled further to make a strong, ginlike liquor. Nigerian breweries also produce several kinds of beer and liquor.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Food plays a central role in the rituals of virtually all ethnic groups in Nigeria. Special ceremonies would not be complete without participants sharing in a meal. Normally it is considered rude not to invite guests to share in a meal when they visit; it is even more so if the visitors were invited to attend a special event such as a marriage or a naming ceremony.

Basic Economy. Until the past few decades, Nigeria had been self-sufficient in producing enough food to feed the population. However, as petroleum production and industry began to boom in Nigeria, much of the national resources were concentrated on the new industries at the expense of agriculture.

Nigeria, which had previously been a net exporter of agricultural products, soon needed to import vast amounts of food it once was able to produce for itself.

Since the 1960s, Nigeria's economy has been based on oil production. As a leading member of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), Nigeria has played a major role in influencing the price of oil on the world market. The oil-rich economy led to a major economic boom for Nigeria during the 1970s, transforming the poor African country into the thirtieth richest country in the world. However, falling oil prices, severe corruption, political instability, and economic mismanagement since then have left Nigeria no better off today than it was at independence.

Since the restoration of civilian rule in 1999, Nigeria has begun to make strides in economic reform. While hopes are high for a strong economic transformation, high unemployment, high inflation, and more than a third of the population living under the poverty line indicate it will be a long and difficult road.

Oil production has had some long-lasting ethnic consequences as well. While oil is Nigeria's largest industry in terms of output and revenue, oil reserves are found only in the Niger Delta region and along the coast. The government has long taken the oil revenues and dispersed them throughout the country. In this way, states not involved in oil production still get a share of the profits. This has led to claims that the minority ethnic groups living in the delta are being cheated out of revenue that is rightfully theirs because the larger ethnic groups dominate politics. Sometimes this has led to large-scale violence.

More than 50 percent of Nigeria's population works in the agriculture sector. Most farmers engage in subsistence farming, producing only what they eat themselves or sell locally. Very few agricultural products are produced for export.

Land Tenure and Property. While the federal government has the legal right to allocate land as it sees fit, land tenure remains largely a local issue. Most local governments follow traditional land tenure customs in their areas. For example, in Hausa society, title to land is not an absolute right. While communities and officials will honor long-standing hereditary rights to areas of land traditionally claimed by a given family, misused or abandoned land may be reapportioned for better use. Land also can be bought, sold, or rented. In the west, the Yoruban kings historically held all the land in trust, and therefore also had a say in how it was used for the good of the community. This has given local governments in modern times a freer hand in settling land disputes.

Traditionally, only men hold land, but as the wealth structure continues to change and develop in Nigeria, it would not be unheard of for a wealthy woman to purchase land for herself.

Major Industries. Aside from petroleum and petroleum-based products, most of the goods produced in Nigeria are consumed within Nigeria. For example, though the textile industry is very strong, nearly all the cloth produced in Nigeria goes to clothing the large Nigerian population.

Major agricultural products produced in Nigeria include cocoa, peanuts, palm oil, rice, millet, corn, cassava, yams, rubber, cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, timber, and fish. Major commercial industries in Nigeria include coal, tin, textiles, footwear, fertilizer, printing, ceramics, and steel.

Trade. Oil and petroleum-based products made up 95 percent of Nigeria's exports in 1998. Cocoa and rubber are also produced for export. Major export partners include the United States, Spain, India, France, and Italy.

Nigeria is a large-scale importer, depending on other countries for things such as machinery, chemicals, transportation equipment, and manufactured goods. The country also must import large quantities of food and livestock. Major import partners include the United Kingdom, the United States, Germany, France, and the Netherlands.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. The highest tier of Nigerian society is made up of wealthy politicians, businessmen, and the educated elite. These people, however, make up only a tiny portion of the Nigerian population. Many Nigerians today suffer under great poverty. The lower classes tend have little chance of breaking from the vicious cycle of poverty. Poor education, lack of opportunities, ill health, corrupt politicians, and lack of even small amounts of wealth for investment all work to keep the lower classes in their place.

In some Nigerian ethnic groups there is also a form of caste system that treats certain members of society as pariahs. The criteria for determining who belongs to this lowest caste vary from area to area but can include being a member of a minority group, an inhabitant of a specific village, or a member of a specific family or clan. The Igbo call this lower-caste group Osu. Members of the community will often discourage personal, romantic, and business contact with any member of the Osu group, regardless of an individual's personal merits or characteristics. Because the Osu are designated as untouchable, they often lack political representation, access to basic educational or business opportunities, and general social interaction. This kind of caste system is also found among the Yoruba and the Ibibios.

Symbols of Social Stratification. Wealth is the main symbol of social stratification in modern Nigeria, especially in urban areas. While in the past many ethnic groups held hereditary titles and traditional lineage important, money has become the new marker of power and social status. Today the members of the wealthy elite are easily identifiable by their fancy clothing and hairstyles and by their expensive cars and Western-style homes. Those in the elite also tend to have a much better command of English, a reflection of the higher quality of education they have received.

Wealth also can be important in marking social boundaries in rural areas. In many ethnic groups, those who have accumulated enough wealth can buy themselves local titles. For example, among the Igbo, a man or a woman who has enough money may claim the title of Ozo. For women, one of the requirements to become an Ozo is to have enough ivory, coral, and other jewelry for the ceremony. The weight of the jewelry can often exceed fifty pounds. Both men and women who want to claim the title must also finance a feast for the entire community.

Political Life

Government. Nigeria is a republic, with the president acting as both head of state and head of government. Nigeria has had a long history of coups d'états, military rule, and dictatorship. However, this pattern was broken on 29 May 1999 as Nigeria's current president, Olusegun Obasanjo, took office following popular elections. Under the current constitution, presidential elections are to be held every four years, with no president serving more than two terms in office. The Nigerian legislature consists of two houses: a Senate and a House of Representatives. All legislators are elected to four-year terms. Nigeria's judicial branch is headed by a Supreme Court, whose members were appointed by the Provisional Ruling Council, which ruled Nigeria during its recent transition to democracy. All Nigerians over age eighteen are eligible to vote.

Leadership and Political Officials. A wealthy political elite dominates political life in Nigeria. The relationship between the political elite and ordinary Nigerians is not unlike that between nobles and commoners. Nigerian leaders, whether as members of a military regime or one of Nigeria's short-lived civilian governments, have a history of doing whatever it takes to stay in power and to hold on to the wealth that this power has given them.

Rural Nigerians tend to accept this noble-peasant system of politics. Low levels of education and literacy mean that many people in rural areas are not fully aware of the political process or how to affect it. Their relative isolation from the rest of the country means that many do not even think of politics. There is a common feeling in many rural areas that the average person cannot affect the politics of the country, so there is no reason to try.

Urban Nigerians tend to be much more vocal in their support of or opposition to their leaders. Urban problems of housing, unemployment, health care, sanitation, and traffic tend to mobilize people into political action and public displays of dissatisfaction.

Political parties were outlawed under the Abacha regime, and only came back into being after his death. As of the 1999 presidential elections, there were three main political parties in Nigeria: the People's Democratic Party (PDP), the All Peoples Party (APP), and the Alliance for Democracy (AD). The PDP is the party of President Obasanjo. It grew out of support for opposition leaders who were imprisoned by the military government in the early 1990s. The PDP is widely believed to have received heavy financial assistance from the military during the 1999 elections. The APP is led by politicians who had close ties to the Abacha regime. The AD is a party led by followers of the late Moshood Abiola, the Yoruba politician who won the general election in 1993, only to be sent to prison by the military regime.

Social Problems and Control. Perhaps Nigeria's greatest social problem is the internal violence plaguing the nation. Interethnic fighting throughout the country, religious rioting between Muslims and non-Muslims over the creation of Shari'a law (strict Islamic law) in the northern states, and political confrontations between ethnic minorities and backers of oil companies often spark bloody confrontations that can last days or even months. When violence of this type breaks out, national and state police try to control it. However, the police themselves are often accused of some of the worst violence. In some instances, curfews and martial law have been imposed in specific areas to try to stem outbreaks of unrest.

Poverty and lack of opportunity for many young people, especially in urban areas, have led to major crime. Lagos is considered one of the most dangerous cities in West Africa due to its incredibly high crime rate. The police are charged with controlling crime, but their lack of success often leads to vigilante justice.

In some rural areas there are some more traditional ways of addressing social problems. In many ethnic groups, such as the Igbo and the Yoruba, men are organized into secret societies. Initiated members of these societies often dress in masks and palm leaves to masquerade as the physical embodiment of traditional spirits to help maintain social order. Through ritual dance, these men will give warnings about problems with an individual's or community's morality in a given situation. Because belief in witchcraft and evil spirits is high throughout Nigeria, this kind of public accusation can instill fear in people and cause them to mend their ways. Members of secret societies also can act as judges or intermediaries in disputes.

Military Activity. Nigeria's military consists of an army, a navy, an air force, and a police force. The minimum age for military service is eighteen.

The Nigerian military is the largest and best-equipped military in West Africa. As a member of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Nigeria is the major contributor to the organization's military branch, known as ECOMOG. Nigerian troops made up the vast majority of the ECOMOG forces deployed to restore peace following civil wars in Liberia, Guinea-Bissau, and Sierra Leone. Public dissatisfaction with Nigeria's participation in the Sierra Leonean crisis was extremely high due to high casualty rates among the Nigerian soldiers. Nigeria pledged to pull out of Sierra Leone in 1999, prompting the United Nations to send in peacekeepers in an attempt stem the violence. While the foreign forces in Sierra Leone are now under the mandate of the United Nations, Nigerian troops still make up the majority of the peacekeepers.

Nigeria has a long-running border dispute with Cameroon over the mineral-rich Bakasi Peninsula, and the two nations have engaged in a series of cross-boarder skirmishes. Nigeria, Cameroon, Niger, and Chad also have a long-running border dispute over territory in the Lake Chad region, which also has led to some fighting across the borders.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

Severe poverty, human rights violations, and corruption are some of the major social ills that have plagued Nigeria for decades. Because Nigeria is in the midst of major political change, however, there is great hope for social reform in the country.

President Obasanjo's administration has been focusing much of its efforts on changing the world's image of Nigeria. Many foreign companies have been reluctant to invest in Nigeria for fear of political instability. Obasanjo hopes that if Nigeria can project the image of a stable nation, he can coax foreign investors to come to Nigeria and help bolster the country's failing economy. The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) are also working with Nigeria to develop economic policies that will revitalize the nation's economy.

Obasanjo also says that rooting out corruption in all levels of government is one of his top priorities.

According to Amnesty International's 2000 report, Nigeria's new government continues to make strides in improving human rights throughout the country, most notably in the release of political prisoners. However, the detention of journalists critical of the military and reports of police brutality continue to be problems. Foreign governments and watchdog organizations continue to press the Nigerian government for further human rights reforms.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. In general, labor is divided in Nigerian society along gender lines. Very few women are active in the political and professional arenas. In urban areas, increasing numbers of women are becoming involved in the professional workforce, but they are greatly outnumbered by their male counterparts. Women who do manage to gain professional employment rarely make it into the higher levels of management.

However, women in Nigeria still play significant roles in the economy, especially in rural areas. Women are often expected to earn significant portions of the family income. As a rule, men have little obligation to provide for their wives or children. Therefore women have traditionally had to farm or sell homemade products in the local market to ensure that they could feed and clothe their children. The division of labor along gender lines even exists within industries. For example, the kinds of crops that women cultivate differ from those that men cultivate. In Igbo society, yams are seen as men's crops, while beans and cassava are seen as women's crops.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. Modern Nigeria is a patriarchal society. Men are dominant over women in virtually all areas. While Nigeria is a signatory to the international Convention on Equality for Women, it means little to the average Nigerian woman. Women still have fewer legal rights than men. According to Nigeria's Penal Code, men have the right to beat their wives as long as they do not cause permanent physical injury. Wives are often seen as little more than possessions and are subject to the rule of their husbands.

However, women can exercise influence in some areas. For example, in most ethnic groups, mothers and sisters have great say in the lives of their sons and brothers, respectively. The blood relationship allows these women certain leeway and influence that a wife does not have.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. There are three types of marriage in Nigeria today: religious marriage, civil marriage, and traditional marriage. A Nigerian couple may decide to take part in one or all of these marriages. Religious marriages, usually Christian or Muslim, are conducted according to the norms of the respective religious teachings and take place in a church or a mosque. Christian males are allowed only one wife, while Muslim men can take up to four wives. Civil official weddings take place in a government registry office. Men are allowed only one wife under a civil wedding, regardless of religion. Traditional marriages usually are held at the wife's house and are performed according to the customs of the ethnic group involved. Most ethnic groups traditionally allow more than one wife.

Depending on whom you ask, polygamy has both advantages and disadvantages in Nigerian society. Some Nigerians see polygamy as a divisive force in the family, often pitting one wife against another. Others see polygamy as a unifying factor, creating a built-in support system that allows wives to work as a team.

While Western ways of courtship and marriage are not unheard of, the power of traditional values and the strong influence of the family mean that traditional ways are usually followed, even in the cities and among the elite. According to old customs, women did not have much choice of whom they married, though the numbers of arranged marriages are declining. It is also not uncommon for women to marry in their teens, often to a much older man. In instances where there are already one or more wives, it is the first wife's responsibility to look after the newest wife and help her integrate into the family.

Many Nigerian ethnic groups follow the practice of offering a bride price for an intended wife. Unlike a dowry, in which the woman would bring something of material value to the marriage, a bride price is some form of compensation the husband must pay before he can marry a wife. A bride price can take the form of money, cattle, wine, or other valuable goods paid to the woman's family, but it also can take a more subtle form. Men might contribute money to the education of an intended wife or help to establish her in a small-scale business or agricultural endeavor. This form of bride price is often incorporated as part of the wooing process. While women who leave their husbands will be welcomed back into their families, they often need a justification for breaking the marriage. If the husband is seen as having treated his wife well, he can expect to have the bride price repaid.

Though customs vary from group to group, traditional weddings are often full of dancing and lively music. There is also lots of excitement and cultural displays. For example, the Yoruba have a practice in which the bride and two or three other women come out covered from head to toe in a white shroud. It is the groom's job to identify his wife from among the shrouded women to show how well he knows his wife.

Divorce is quite common in Nigeria. Marriage is more of a social contract made to ensure the continuation of family lines rather than a union based on love and emotional connections. It is not uncommon for a husband and wife to live in separate homes and to be extremely independent of one another. In most ethnic groups, either the man or the woman can end the marriage. If the woman leaves her husband, she will often be taken as a second or third wife of another man. If this is the case, the new husband is responsible for repaying the bride price to the former husband. Children of a divorced woman are normally accepted into the new family as well, without any problems.

Domestic Unit. The majority of Nigerian families are very large by Western standards. Many Nigerian men take more than one wife. In some ethnic groups, the greater the number of children, the greater a man's standing in the eyes of his peers. Family units of ten or more are not uncommon.

In a polygamous family, each wife is responsible for feeding and caring for her own children, though the wives often help each other when needed. The wives also will take turns feeding their husband so that the cost of his food is spread equally between or among the wives. Husbands are the authority figures in the household, and many are not used to their ideas or wishes being challenged.

In most Nigerian cultures, the father has his crops to tend to, while his wives will have their own jobs, whether they be tending the family garden, processing palm oil, or selling vegetables in the local market. Children may attend school. When they return home, the older boys will help their father with his work, while the girls and younger boys will go to their mothers.

Inheritance. For many Nigerian ethnic groups, such as the Hausa and the Igbo, inheritance is basically a male affair. Though women have a legal right to inheritance in Nigeria, they often receive nothing. This is a reflection of the forced economic independence many women live under. While their husbands are alive, wives are often responsible for providing for themselves and their children. Little changes economically after the death of the husband. Property and wealth are usually passed on to sons, if they are old enough, or to other male relatives, such as brothers or uncles.

For the Fulani, if a man dies, his brother inherits his property and his wife. The wife usually returns to live with her family, but she may move in with her husband's brother and become his wife.

Kin Groups. While men dominate Igbo society, women play an important role in kinship. All Igbos, men and women, have close ties to their mother's clan, which usually lives in a different village. When an Igbo dies, the body is usually sent back to his mother's village to be buried with his mother's kin. If an Igbo is disgraced or cast out of his community, his mother's kin will often take him in.

For the Hausa, however, there is not much of a sense of wide-ranging kinship. Hausa society is based on the nuclear family. There is a sense of a larger extended family, including married siblings and their families, but there is little kinship beyond that. However, the idea of blood being thicker than water is very strong in Hausa society. For this reason, many Hausas will try to stretch familial relationships to the broader idea of clan or tribe to diffuse tensions between or among neighbors.

Socialization

Infant Care. Newborns in Nigerian societies are regarded with pride. They represent a community's and a family's future and often are the main reason for many marriages.

Throughout Nigeria, the bond between mother and child is very strong. During the first few years of a child's life, the mother is never far away. Nigerian women place great importance on breast-feeding and the bond that it creates between mother and child. Children are often not weaned off their mother's milk until they are toddlers.

Children who are too young to walk or get around on their own are carried on their mother's backs, secured by a broad cloth that is tied around the baby and fastened at the mother's breasts. Women will often carry their children on their backs while they perform their daily chores or work in the fields.

Child Rearing and Education. When children reach the age of about four or five, they often are expected to start performing a share of the household duties. As the children get older, their responsibilities grow. Young men are expected to help their fathers in the fields or tend the livestock. Young women help with the cooking, fetch water, or do laundry. These tasks help the children learn how to become productive members of their family and community. As children, many Nigerians learn that laziness is not acceptable; everyone is expected to contribute.

While children in most Nigerian societies have responsibilities, they also are allowed enough leeway to be children. Youngsters playing with homemade wooden dolls and trucks, or groups of boys playing soccer are common sights in any Nigerian village.